The Rake's Progress

Composed by

Igor Stravinsky

Libretto by

W. H Auden

Conducted by

Esa-Pekka Salonen

Directed by

Peter Sellars

Scene Designer:

Adrianne Lobel

Lighting Designer:

James F. Ingalls

Produced by:

Theatre Musical de Paris- Chatelet, Paris, France

Venue:

Theatre Musical de Paris-Chatelet

Year:

1996

In my work with Peter Sellars I have always been aware of the dangers of trying to make a complex work of art fit a contemporary headline. But as an artist I see theater as a form of public discourse, such as was practiced in Ancient Greece, and today’s discourse is deeply influenced by headlines. Our choice of the contemporary milieu has allowed us to maintain an active engagement with our audiences. By presenting current conflicts in universal context while highlighting their contemporary political resonance, we invite the audience to step out of their comfort zone and contemplate their choices as human beings. We also work to attract constituencies whose life experiences resonate with the content of the productions, hence, for example, the war veterans who were invited to attend our production of Handel’s Hercules at the Chicago Lyric Opera in March 2011, and who participated in a discussion centering on post-traumatic stress in the military and its results on veterans and their families. The trauma and madness of war is surely not singular to Ancient Greece or to 18th century England. The costumes for Hercules placed up-to-date American military uniforms next to dresses and shawls that traced their inspiration to contemporary Afghanistan as well as Ancient Greece and 18th century England. We also explored the topic of war in Ajax (1986), The Persians (1993), and Winds of Destiny (2011).

In Rake’s Progress we explored American “love affair” with prisons. To many people around the world it is difficult to comprehend that a democratic country such as ours jails so many men and women, and even more specifically, have a prison population with disproportionately large numbers of men from African American and Hispanic communities.

The title and inspiration for this opera are engravings created by English 18th century artist, William Hogarth. These engravings illustrate the life of Tom Rakewell, son of a rich merchant who spirals into depravity by spending money on empty pursuits such as gambling, and prostitutes. In the opera he keeps company with Nick Shadow, who is devil himself. Tom Rakewell ends up in London’s infamous mental hospital, Bedlam. His love, Anne Trulove, tries to comfort him but he dies alone.

Peter Sellars translated the action of the opera into contemporary life. Tom Rakewell does not end up in an insane asylum (since we no longer have those) but, more appropriately, he ends up in jail as does Nick.

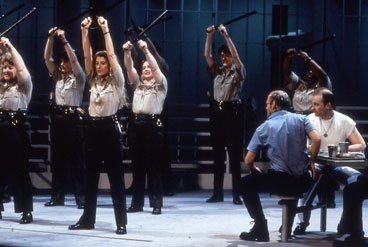

Our source of visual research was California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, the name which says it all. Adrianne Lobel, scene designer, specifically looked at the women’s facility in Chino. In our production, Peter decided that the prison guards were all women, while the inmates were all men. This use of female prison guards created and interesting contrast to Anne Truelove’s character.

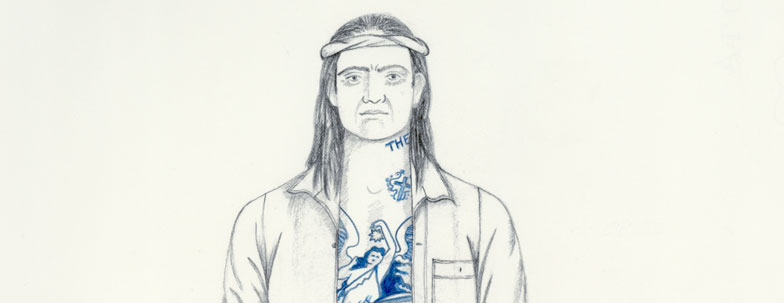

I designed the prison inmates with tattoos which are an important part of American prison life today. We faced an interesting challenge in having to create removable tattoos which needed to be very large and very complex. Our production opened at Theatre Musical de Paris-Chatelet, in Paris, a facility that was able to find excellent make-up artists who created stencils and applied the tattoos for every performance.

Next production, Ah, Wilderness!