Doctor Atomic

Composed by

John Adams

Libretto by

Peter Sellars

Directed by

Peter Sellars

Scene Designer:

Adrianne Lobel

Lighting Designer:

James F. Ingalls

Producer:

Opera was commissioned and co-produced by

San Francisco Opera, San Francisco, California,

De Nederlandse Opera, Amsterdam, Holland, and

Chicago Lyric Opera, Chicago, Illinois

BBC Opus Arte recorded the production in 2008

at De Nederlandse Opera.

This performance was also broadcast on

Nederlandse Publieke Omroep (NPO)

(English: Netherlands Public Broadcasting) - September 2008

Venue:

San Francisco Opera, De Nederlandse Opera,

and Chicago Lyric Opera

Year:

2005

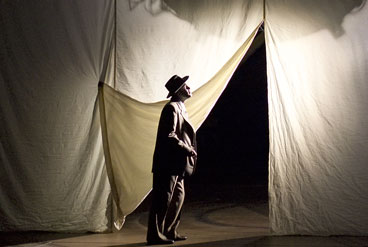

The first nuclear explosion took place at a site named "Trinity" in New Mexico in the early morning hours of July 16, 1945. The man who chose the name "Trinity" was J. Robert Oppenheimer, a complex and conflicted man even before he signed up to lead a team of scientists to supply mankind with means of its own complete destruction.

In his effort to transmute the bomb from a weapon of death to an instrument of peace he invoked the substance of two poems by John Donne: "Hymne to God My God, in My Sicknesse" and Sonnet XIV from "Holy Sonnets". That such a man, one who was driven to transcend the limits of human scientific knowledge, and who also had profound understanding of an artists' quest to attain the realm of higher truth, should become subject of an opera is perhaps not surprising. It was Pamela Rosenberg (then the General Director of San Francisco Opera) who had the inspiration to create an opera about Oppenheimer as part of cycle of works devoted to exploring the Faustian legend.

Pamela Rosenberg approached the Pulitzer Prize winning composer John Adams with the idea to compose an opera and he in turn asked Peter Sellars to collaborate on the project.

In this instance, Peter Sellars not only directed the premiere of Doctor Atomic but he also created the libretto. The libretto reflects Peter's perception of the value art has in helping us fathom the depths of seemingly contradictory human impulses as well as the complexities of seminal historical events such as the creation of the atomic bomb.

The Doctor Atomic libretto contains material that on the surface seems disconnected: poetry of Muriel Rukeyser (forming most of Kitty Oppenheimer's arias), formerly classified documents obtained from the United States National Archives (woven into arias of the scientists), John Donne's “Holy Sonnet XIV” (as the text of the aria Oppenheimer sings during the most self-reflective moment in the opera), excerpts from the “Bhagavad-Gita” (sung by the chorus), and poetry of Charles Baudelaire, among others. These seemingly unrelated materials are used to illuminate the personal, political and scientific contradictions and paradoxes that Oppenheimer, the Los Alamos scientists, their wives, and children, the military and the workers experienced during the construction of the first atomic bomb.

My work on Doctor Atomic began with extensive study of the libretto and its sources. For me a successful collaboration depends on designer's and director's ability to fully internalize the work of art that they have been commissioned to stage. This is because what designers and directors do is not illustrate, or explain. Instead, we engage in creation of a new work of art in response to a work of art. In addition, in a close long standing collaboration such as I have with Peter Sellars, we both rely on my readiness to go beyond the obvious at the first meeting. To not start the dialogue on the same level would endanger the collaboration.

In addition to studying the work of Muriel Rukeyser, John Donne, and other materials, I also had to learn as much as possible about the main characters in the opera: J. Robert Oppenheimer, his wife Kitty, Hungarian scientists Edward Teller, young Robert Wilson, and General Leslie Groves. I also had to discover more about the people who supported the research and life at Los Alamos and who comprise the chorus in Doctor Atomic, the many scientists involved in the work on the bomb, their wives, members of the Army Corps of Engineers' Special Engineering Detachment (SED), Military Police that guarded the site, and the mostly Native American maids and maintenance men, many of whom were from the Tewa tribe.

The chorus plays a pivotal role in all of John Adams' operas. In Doctor Atomic the chorus represents not only those who participated in the creation of the atomic bomb, but also mankind as a whole. Early on in the design process I traveled to New Mexico and visited the National Atomic Museum in Albuquerque, Los Alamos Historical Society, and the Bradbury Science Museum, Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe (for research of the Native American clothing), and the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology Mineralogical Museum in Socorro (not far from the explosion site).

It was at this small museum that I found some of my inspiration for the color palette which is one of the most important elements in my design work. The Mineralogical Museum has a large collection of New Mexico specimens, some from areas near the explosion site. During my visit to Socorro, I also collected native grasses, leaves and stones. I eventually also drew inspiration from a color photograph of the ironically named Jornada del Muerto taken on July 15, 1945, a day before the explosion.

To choose the appropriate color is especially important for opera designs. Color's effect on the mind can be compared to music's impact on the mind. Because the Doctor Atomic scene designer, and lighting designer and I have previously worked together on many productions, the opera unfolded as a series of unforgettable visuals where the bodies of the people, scenic elements and lighting formed a rich emotional response to the music.

In my effort to find out as many details as possible about the people of Los Alamos I was greatly helped by a unique website called "Children of the Manhattan Project", where former residents and their descendants have posted numerous photographs from Los Alamos and the other Manhattan Project sites. It is ironic that though the U.S. government expended a great deal of energy on keeping Los Alamos’ secret during its brief existence as an atomic bomb development site, its "inmates" took hundreds of snap shots documenting their secret lives which are now posted on the internet.

When creating a work of art based on lives of those who may still be amongst us or whose families may still be alive, an artist must be careful to miss nothing, because a small thing may contain within it something that has deep meaning to them. After inquiring about the design of certain badges worn by the SED at Los Alamos as well as metal buttons worn by scientists, seen in numerous photographs from the site of the explosion, my assistant received the following e-mail from Hedy Dunn, the director of Los Alamos Historical Society: "Your questions are amazing...in fact so amazing that most we had never contemplated before. I do appreciate your quest for accuracy, but perhaps some of these details have been lost to history."

In fact, they were not lost to history. We contacted several of the scientists who worked at Los Alamos and were still alive and received answers from two of them: John Balagna, an analytical chemist and Ben Diven, a physicist. This is a letter from John Balagna: "Badges were in two colors: white badges for staff members (tech degrees, BS, and PhD), and also for need-to-know level. A white badge got you into the weekly colloquium. Blue badges were for technicians, secretaries and others. White barges had a thin black circle ¼ “from circumference. All badges had a number. Mine was H-6."

After gathering the research, absorbing the work itself, after the information has been assimilated and internalized, the design of the costumes is comparatively easy. I use photographs and measurements of singers if available before I begin drawing but for a project like this where we were referencing people whose faces were relatively well-known, I often draw the face and body type authentically to inspire the actors or singers to create the characters.

However a designer's largest challenge is to transform one dimensional rendering into costumes worn by real singers. All but a fraction of the costume designs were built not purchased. Many of the fabrics were dyed and/or painted. Every member of the chorus, dancers and supers (non-singing actors) had his or her individual costume; no two costumes were completely alike.

Doctor Atomic received a large amount of attention as one of the most important music events of the year. San Francisco Opera collaborated with other institutions to create a series of unique educational ancillary events which started in August 2005 and continued till October, 2005 There were several events co-sponsored with UC Berkeley's The Consortium for the Arts & Arts Research Center, one of which was “Science and the Soul: Robert Oppenheimer and Doctor Atomic ", a panel with Peter Sellars, John Adams, UC Berkeley Dean of Physical Sciences Mark Richards and Pamela Rosenberg. There were also events related to Doctor Atomic at the C. G. Jung Institute of San Francisco, Stanford Institute for International Studies, and American Physical Society. Furthermore, the creation of Doctor Atomic was the subject of a documentary film: "Wonders Are Many: The Making of Doctor Atomic" directed by Jon Else, whose credits include an award-winning documentary on Oppenheimer and the Manhattan Project. The film was subsequently screened at a number of major film festivals, including the 2007 San Francisco International Film Festival.

It is rewarding to be part of creation of a new work of art, even as ephemeral as opera is by its very nature. I firmly believe that it is the designer's job to call attention to the music and to the libretto, the singers, the orchestra, the dancers, and not to the costumes. I am most gratified when the audience experiences the opera without having to work to integrate the elements. Designing costumes for Doctor Atomic was especially difficult, because I was asked to be even more subtle in my approach than usual. This is because the opera is haunted by ghosts of so many: the thousands and thousands who died and suffered in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the scientists and military men and women who were directly and indirectly responsible for unimaginable and unprecedented horror and suffering, and the sensitive, refined and brilliant man who perhaps did sell his soul to the devil, J. Robert Oppenheimer.